From the Way of the Fathers

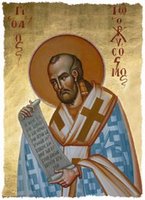

From the Way of the FathersGolden Mouth

John Chrysostom (349-407) was a talented young man, the son of a government official who died when John was still a baby, leaving his wife a widow and single mother at age twenty. John’s mother made great sacrifices so that her son could study under the world’s most famous professor of rhetoric, the pagan Libanios of Antioch. John became his star pupil.

At eighteen, John discerned a call to dedicate himself entirely to the service of the Church. He placed himself under the tutelage of the renowned Scripture scholar, Diodore of Tarsus. Soon, once again, John was the most brilliant pupil of his master.

He decided, however, that he was interested in contemplation more than career, and so he stepped out of track for clerical orders and, in early adulthood, went off into a mountain cave, where he lived a hermit’s life for two years, till his health gave out.

When John returned to Antioch, his bishop ordained him first a deacon and then a priest. For twelve years, he was the main preacher in the city’s cathedral church. There, he preached the homilies that earned him his fame. He also served as vicar general for the metropolitan see.

It was his fame as a preacher, however, that brought him to the attention of the wider Church, and especially the imperial court. Thus, when the patriarch of Constantinople died, the emperor unexpectedly summoned John from Antioch to the most powerful bishop’s throne in the East. John declined the honor. But the emperor ordered that John be taken by force or subterfuge, if necessary, and so he was.

John’s habitual honesty and integrity did not serve him well, by capital standards. He was a reformer and an ascetic, demanding much of others, but even more of himself. The clergy of Constantinople were not, however, eager to be reformed or to imitate John’s spartan lifestyle. Nor was the imperial family — especially the empress — interested in John’s advice about their use of cosmetics, their lavish expenses, and their self-aggrandizing monuments. John found it outrageous that the rich could relieve themselves in golden toilet bowls while the poor went hungry. He reached the limits of his patience when the empress went beyond the law to seize valuable lands from a widow, after the widow had refused to sell the property. (John did not miss the opportunity to cite relevant Old Testament passages, like 1 Kings 21.)

Ordinary people found inspiration, solace, and — no doubt — entertainment in the great man’s preaching. But the powerful were not amused. They arranged a kangaroo court of bishops to depose John in 403. In fact, a military unit interrupted the liturgy on Easter Vigil, just as John was preparing to baptize a group of catechumens. Historians record that the baptismal waters ran red with blood.

John was sent away to the wild country on the eastern end of the Black Sea. His health was never good, and his guards took advantage of this. In moving him to a new location, they forced him to go on foot. They marched him to death in September 407.

Yet, immediately, he received popular veneration as a saint. Within a generation, a new emperor was welcoming the return of St. John Chrysostom’s relics to Constantinople.

Chrysostom is not a name John received from his parents. It was the name he earned from the congregations who loved him. Chrysostomos means “Golden Mouth” in Greek.

There’s an excellent online clearinghouse of works by an about St. John. I’ve posted some excerpts of his homilies here, here, and here. A good biography of St. John is J.N.D. Kelly’s Golden Mouth: The Story of John Chrysostom-Ascetic, Preacher, Bishop.

John Chrysostom (349-407) was a talented young man, the son of a government official who died when John was still a baby, leaving his wife a widow and single mother at age twenty. John’s mother made great sacrifices so that her son could study under the world’s most famous professor of rhetoric, the pagan Libanios of Antioch. John became his star pupil.

At eighteen, John discerned a call to dedicate himself entirely to the service of the Church. He placed himself under the tutelage of the renowned Scripture scholar, Diodore of Tarsus. Soon, once again, John was the most brilliant pupil of his master.

He decided, however, that he was interested in contemplation more than career, and so he stepped out of track for clerical orders and, in early adulthood, went off into a mountain cave, where he lived a hermit’s life for two years, till his health gave out.

When John returned to Antioch, his bishop ordained him first a deacon and then a priest. For twelve years, he was the main preacher in the city’s cathedral church. There, he preached the homilies that earned him his fame. He also served as vicar general for the metropolitan see.

It was his fame as a preacher, however, that brought him to the attention of the wider Church, and especially the imperial court. Thus, when the patriarch of Constantinople died, the emperor unexpectedly summoned John from Antioch to the most powerful bishop’s throne in the East. John declined the honor. But the emperor ordered that John be taken by force or subterfuge, if necessary, and so he was.

John’s habitual honesty and integrity did not serve him well, by capital standards. He was a reformer and an ascetic, demanding much of others, but even more of himself. The clergy of Constantinople were not, however, eager to be reformed or to imitate John’s spartan lifestyle. Nor was the imperial family — especially the empress — interested in John’s advice about their use of cosmetics, their lavish expenses, and their self-aggrandizing monuments. John found it outrageous that the rich could relieve themselves in golden toilet bowls while the poor went hungry. He reached the limits of his patience when the empress went beyond the law to seize valuable lands from a widow, after the widow had refused to sell the property. (John did not miss the opportunity to cite relevant Old Testament passages, like 1 Kings 21.)

Ordinary people found inspiration, solace, and — no doubt — entertainment in the great man’s preaching. But the powerful were not amused. They arranged a kangaroo court of bishops to depose John in 403. In fact, a military unit interrupted the liturgy on Easter Vigil, just as John was preparing to baptize a group of catechumens. Historians record that the baptismal waters ran red with blood.

John was sent away to the wild country on the eastern end of the Black Sea. His health was never good, and his guards took advantage of this. In moving him to a new location, they forced him to go on foot. They marched him to death in September 407.

Yet, immediately, he received popular veneration as a saint. Within a generation, a new emperor was welcoming the return of St. John Chrysostom’s relics to Constantinople.

Chrysostom is not a name John received from his parents. It was the name he earned from the congregations who loved him. Chrysostomos means “Golden Mouth” in Greek.

There’s an excellent online clearinghouse of works by an about St. John. I’ve posted some excerpts of his homilies here, here, and here. A good biography of St. John is J.N.D. Kelly’s Golden Mouth: The Story of John Chrysostom-Ascetic, Preacher, Bishop.

No comments:

Post a Comment